I’ve had the rough outlines of this post in my head for some time, and many of the things I’ll mention here will be familiar to my friends, who will have heard me say similar things in person, so it’s a coincidence that the issue of British Pakistani rape gangs has flared up on X/Twitter in the past few weeks. Rotherham, Rochdale et al is the perfect illustration of how Western multicultural ideology has been able to override common sense and basic justice.

While I think it’s fair to say we’ve done better than the UK in integrating migrants (although one suspects much has been swept under the rug) we run the same risks that the British state now faces: the total disintegration of the state’s legitimacy and a consequent risk of collapsing into total dysfunction.

As with much else wrong in our country, the root cause of the present issue is the huge disconnect between the desires of the bulk of the Australian population and the desires of the bureaucratic caste which directs government policy. This cleavage is particularly pronounced when it comes to issues such as immigration and cultural policy. A cosmetic cosmopolitanism is almost the defining cultural attitude of succeeding in our major public and private institutions but this is an attitude not shared by most of the Australian population (unsurprisingly as it’s not really an attitude shared by any large population in all of human history).

With the abolition of the White Australia Policy and the imposition of official Big-M Multiculturalism the cosmopolitan bureaucrats won the day but it was on false premises. I think it’s fair to say Australians did consent to a softening of internal cultural policing so that non-white newcomers could hang onto some of their more cosmetic customs during a period of adjustment and integration (food, dress and dance).

But they didn’t consent to the creation of long-term, powerful ethnic lobbies and ghettos, the denigration of the native culture via our educational institutions or the wholesale transformation of the Australian demography away from one that was predominantly white and indeed, British. Despite official pronouncements, assimilation was assumed as what would happen.

The kind of assimilation Australians were comfortable with was only really possible with a small migrant intake, taken over very long time frames and with the kind of cultural adoption that usually entails some degree of intermarriage.

This was the premise upon which large-scale active resistance to the abolition of the White Australia Policy was avoided, but even then, there were waves of defiance that, while increasingly spasmodic (cut off as they were from elite support), over time become increasingly focused on ‘the national question’.

First was the crushing defeat of the Whitlam government at the hands of Malcolm Fraser’s Liberals, which was a more general purpose reaction to leftist overreach, of which the imposition of multiculturalism was a signal component.

Then came the eighties and John Howard’s flirtation with re-introducing a minimum degree of selective discrimination in immigration, simultaneous with Geoffrey Blainey’s dissent against multiculturalism from the academy.

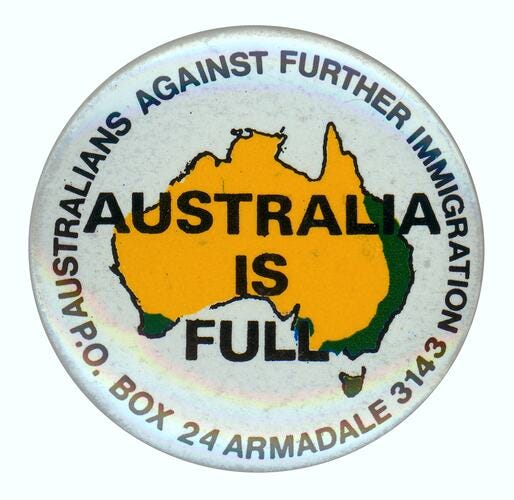

In the nineties, the middle class Australians Against Further Immigration (AAFI) gave way to the working class reaction of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, the energy of which was largely absorbed by Howard’s Liberal Party, through sheer popularity forging a new bipartisan consensus on an extremely strict asylum policy (which is still looked upon as the gold standard by nationalist parties in Europe) while conducting a bait-and-switch on the Australian population that saw ‘the planes’ ramp up even as ‘the boats’ were stopped.

Finally, the 2005 Cronulla riots were a spontaneous, street-level reaction to official non-action against aggressively anti-social and criminal behaviour by Lebanese Muslims, one of the standout groups for their difficulty in assimilating to Australian culture.

As the Voice Referendum showed though, while Australian resistance to multiculturalism was dampened, it didn’t disappear and in fact, is stronger than many might have suspected. The Australian population can still register its disagreement with anti-national initiatives wherever democratic means enable it to do so, even if those opportunities have been increasingly limited.

Cronulla may end being seen as the apogee of the bureaucratic state’s ability to police mainstream desires on immigration and multiculturalism1. A further public reckoning was delayed by the China-induced commodities boom, which papered over the cracks in our spluttering economic model, but that trick is starting to wear off.

Recognition is growing that assimilation of the kind Australians acquiesced to in the last quarter of the 20th century has become increasingly difficult as advances in technology means a new migrant need never leave the ‘infosphere’ of their home country. The Italian migrant in the fifties in many cases never saw Italy again, and apart from the odd letter from home, or Italian newspaper, was largely cut off and was forced to adapt to their new environment.

For the immigrant who comes to Australia now it is entirely different: they will remain in touch with their home culture through the internet, indeed most of their cultural consumption will likely remain unchanged. For groups such as Indians, Nepalese and Chinese who come here in large numbers, the current policy amounts to the creation of de facto foreign colonies on our soil. The fact that these people are hard-working or ‘nice’ does not change this basic fact. Assimilation has been abandoned.

The technological advances have simultaneously empowered resistance to mass immigration, with social media increasingly allowing Australians to bypass traditional media gatekeepers. New voices have arisen from unexpected quarters: tech barons, moderate social democrats and youth influencers. The reaction is not purely based on the idea of cultural fit - the new concerns are tied to immigration’s central role in propping up the property Ponzi which is destroying the Australian ideal of a property-holding democracy.

It remains to be seen whether the decentralised resistance to mass immigration will force a restoration of common sense in our policy settings. Without a substantial course correction we’re staring down the barrel of Lebanonisation: a dysfunctional state riven by conflict between ethnic blocs.

The nation-state is one of the most effective human institutions for the furtherance of collective goals, but without an actual nation it loses much of its internal coherence.

The supreme irony of our current trajectory is that the greatest proponents of bureaucratic multiculturalism has been the social-democratic left, who have, by far, the most to lose from the death of the nation-state. The nationalist right will be hyper-charged by a world of zero-sum ethnic competition. The libertarian right will be ecstatic at the collapse of the welfare state which is likely to accompany a collapse into sub-national loyalties.

As we’ve come to expect from the left, a performative cosmopolitanism will always overcome any other of their stated goals like income equality or solidarity. It seems likely that any restoration of the centrality of the nation-state in Australian public life will have to come from the right.